LINEAGES

Kristine Barrett & Debbie Barrett-Jones

Leedy-Voulkos Art Center, Kansas City, MO 2023 - Weavings, video/sound installation, mixed-media installations

Anchoring the project are a set of family objects or sites, “traces” between Sweden (representing the artists’ matrilineal ancestry) and the United States (where both artists were born and raised). Each of these articulate a multitude of lineages, histories, geographies, and entangled identities. None of the objects or sites exist as entities in and of themselves, rather, they can be viewed as nodes in an ever-shifting, open-ended network of complex relationships. As such, the artists present genealogies as materially constructed narratives—anchored in objects, processes, bodies, and places. This materiality also relates to the ways we in-hvabit place, or multiple places simultaneously, and how those places in turn inhabit us—leaving traces within each person. The art works presented are as much about the process of making as they are reflective of the materiality of the sites in which they were created (and conceptualized through). When weaving, we actively engage in this construction as process—continually making choices that include some things and exclude others. Likewise, this process directly relates to Swedish American identities—borderlands—constantly being (re)woven, (re)membered, and (re)articulated within a polyphony of materials, practices, experiences, associations, and geographies.

ANCHOR OBJECTS

FAMILY WEAVINGS

Two Swedish weavings brought from Sweden by the artists’ great-grandmother when emigrating or possibly during her return visit in 1957. Both objects use a compound twill derivative woven structure. Family Weaving I: Early to mid-20th Century northern Sweden or Norway; handwoven, wool, wool/linen blend. Point twill / diamond twill with open weft threads. Threads connecting across distances, more vulnerable exposed, subject to breakage/severing (and if need be, re-connected). Family Weaving II: Early to mid-20th century Sweden; handwoven, cotton. Rosegång / rosepath weave, a quintessentially ‘Swedish’ woven structure found throughout the country, and particularly in Jämtland.

Both sisters use compound weaves point twill and tabby (plain weave), which historically in Sweden would have been used for practical purposes as everyday cloth (upholstery, table cloths, rags, bed covers, and so on). We use them differently, reconceptualized in each woven work—in ways our forebearers wouldn’t have been able. Particularly in regards to the interview considered here.

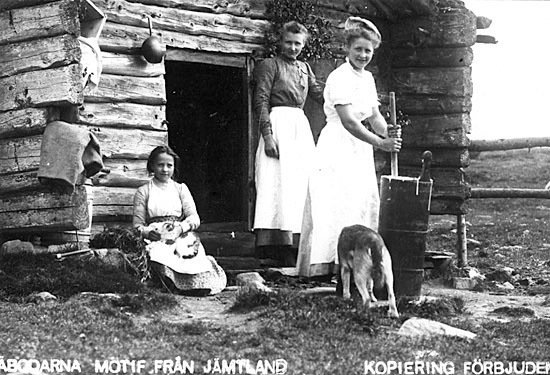

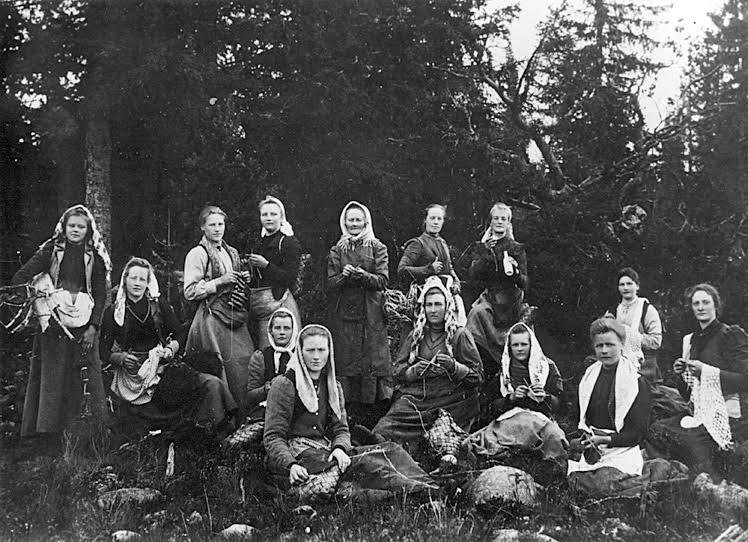

FÄBOD FAMILY PHOTOS

Photos by Nils Thomasson/Fäbodarna Jämtland: 1902 family portrait at a fäbod on Oviksfjällen. Photo by Nils Thomasson. The fäbods in this area of Oviksfjällen (Ovik’s Mountain) were used as summer farms between midsommar and the end of August, and as Sámi reindeer herding grounds the rest of the year. In central/northern areas of Sweden, women (kullor or vallkullor) took cattle and goats into the mountains and forests where they would spend 2-4 months every summer grazing, milking, and making various dairy products (as well as a set amount of textiles, knitted and embroidered). Arable land was scarce and the growing season extremely limited due to the long winters (in some areas the growing season was only 2-3 months). Therefore, Swedes in the area (including our matrilineal ancestors) depended on dairy products, both for sustenance and the market to maintain themselves through the winter. Dairy products constituted up to 15-25% of their yearly caloric intake. The same farms were used outside of the summer season for reindeer herding and grazing by the local indigenous people who have inhabited areas of Scandinavia for at least 10,000 years.

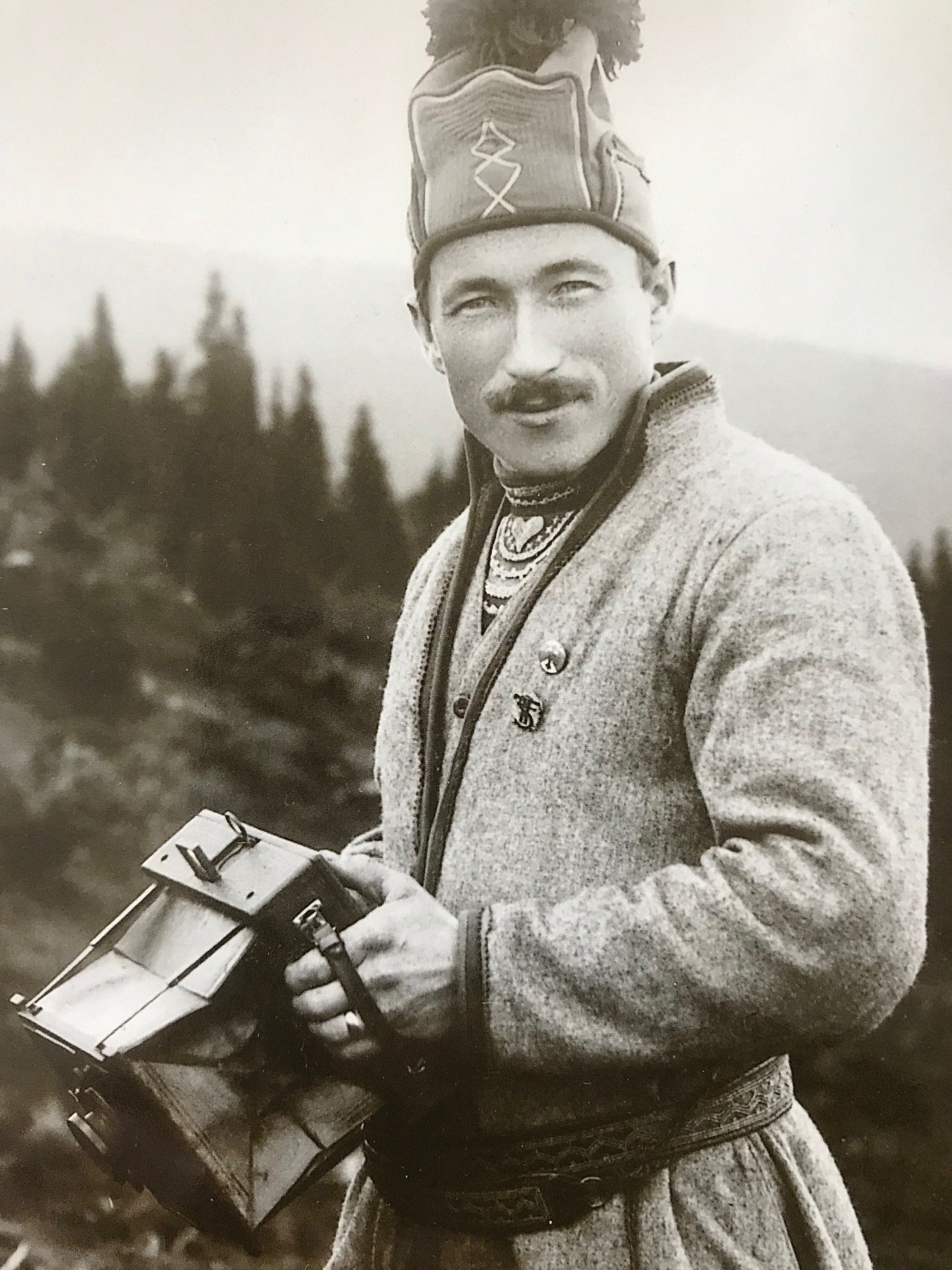

Nils Thomasson was a close family friend and famous Sámi photographer throughout Jämtland, or southern Saepmi. He was responsible for much of the ethnographic photographs taken in early 20th century Jämtland (currently housed within the massive Jamtli county museum archive), and was also considered an advocate and cultural ambassador for the local Sámi, who were often marginalized, disenfranchised, and colonized by the broader Swedish state.

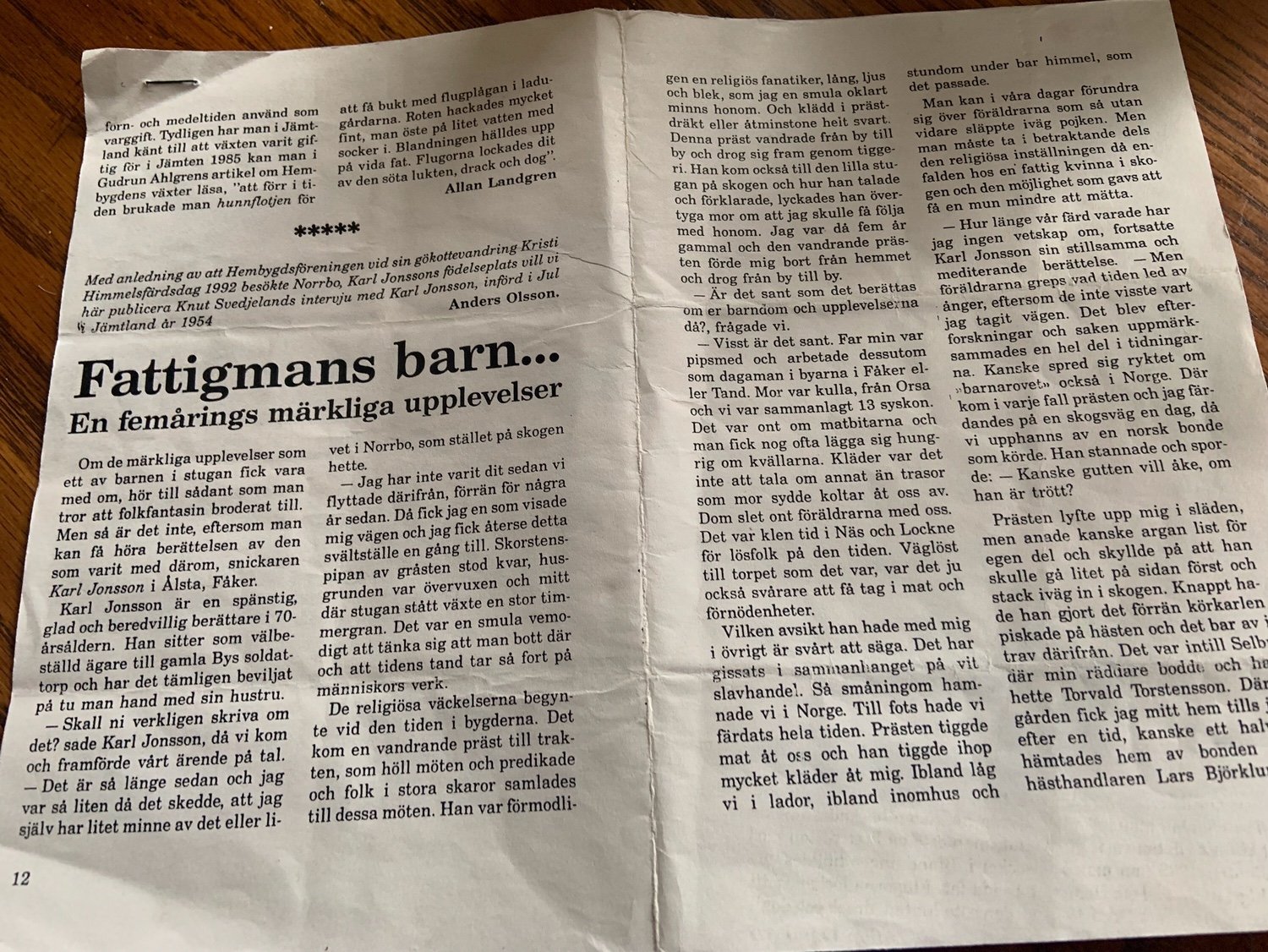

ARCHIVAL INTERVIEW - SWEDEN

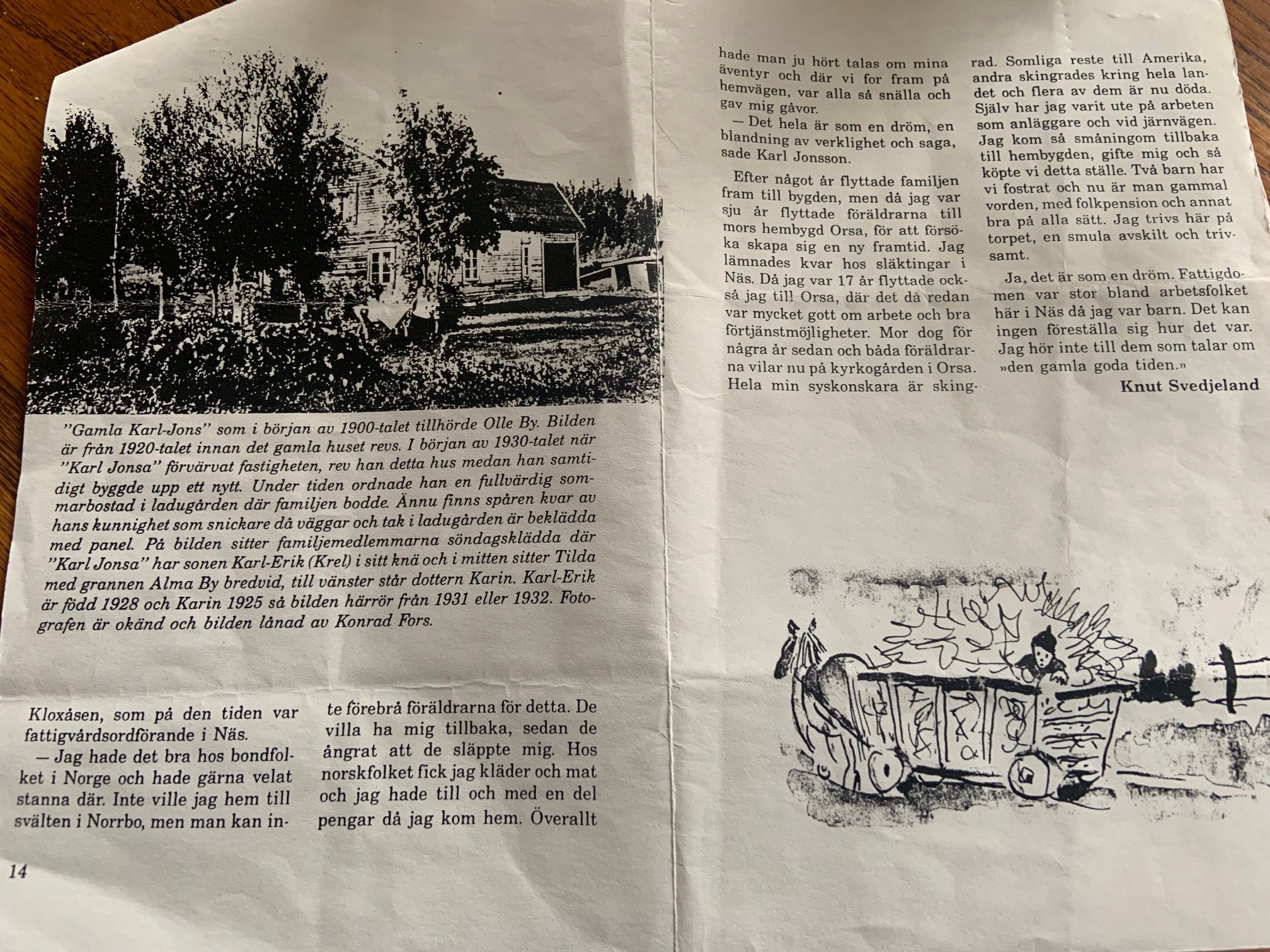

"Poor Man's Child...A Five Year-old's Strange Experience" Interview with Karl Jonsson: Originally recorded in 1954 in Jämtland as part of the county archives, and republished in 1992 in Östersund (the main urban center in Jämtland). The interview is with the artists’ great-great uncle (brother to their great-grandfather who emigrated to the U.S.) detailing the impoverished conditions that resulted in his being kidnapped and nearly sold by an itinerant wandering priest—walking from Sweden to coastal Norway. A striking recurring theme is Karl Jonsson’s fixation on the lack of cloth and clothing rather than hunger (though they were in the midst of a famine when the incident took place):

“…we were a total of 13 siblings. Bits of food were scarce and you often had to go to bed hungry in the evenings. There were no clothes to speak of other than rags shared between us that mother sewed together…What intention he [the priest] had with me is difficult to say. It has been speculated he was connected to the white slave trade. Eventually we ended up in Norway. We had traveled on foot the entire time. The priest begged food for us and he begged a lot for clothes for me.”

The photocopied document was found amongst our grandmother’s possessions when she died. Other like documents included letters, newspaper clippings, photocopied stories, and photos from family in Sweden. In many ways, our grandmother was the last remaining link between Sweden and the US. Her death constituted a severing of threads linking two portions of our family—one in Sweden and the other in America. The effect of this fissure is tangible and material.

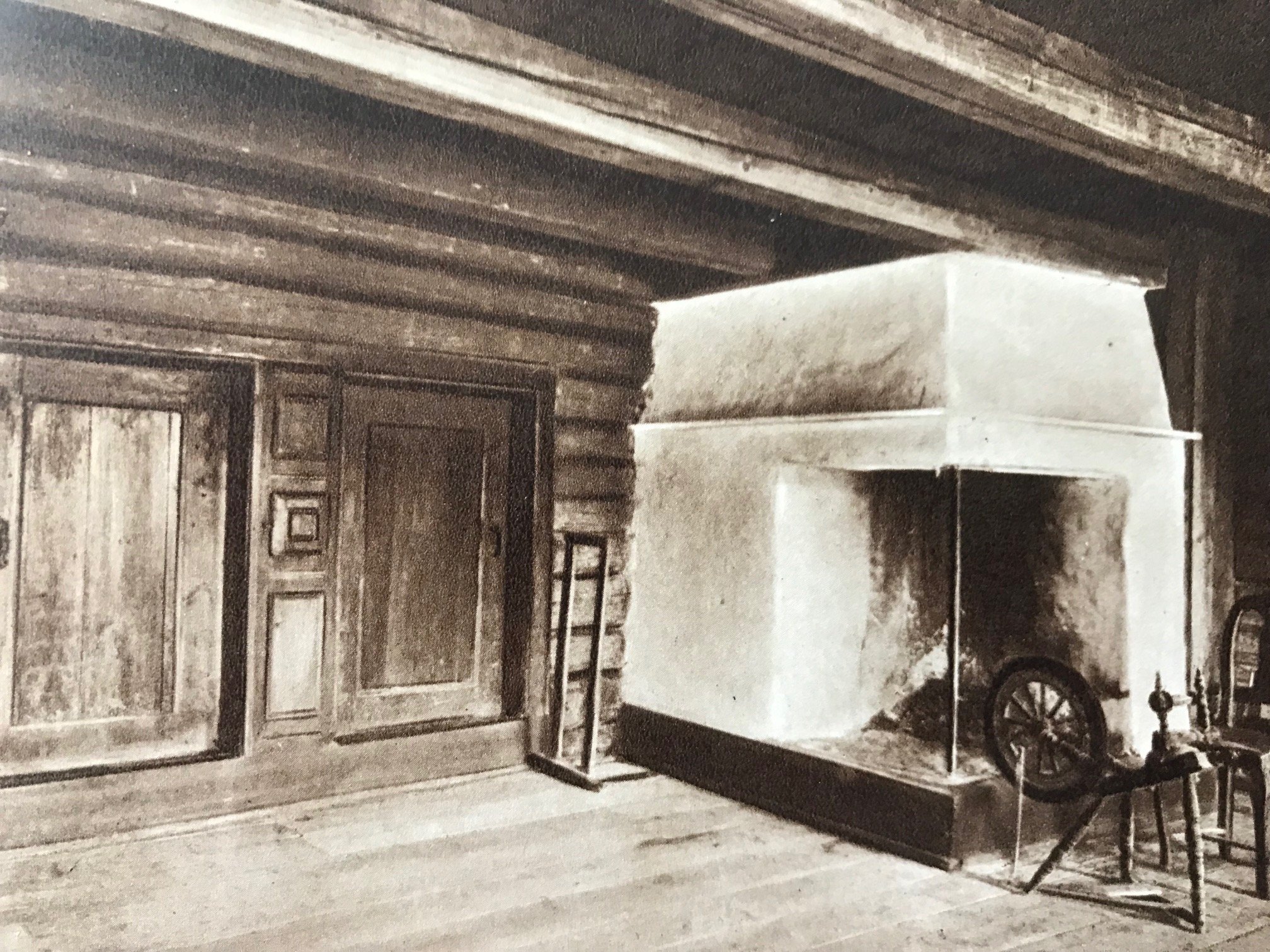

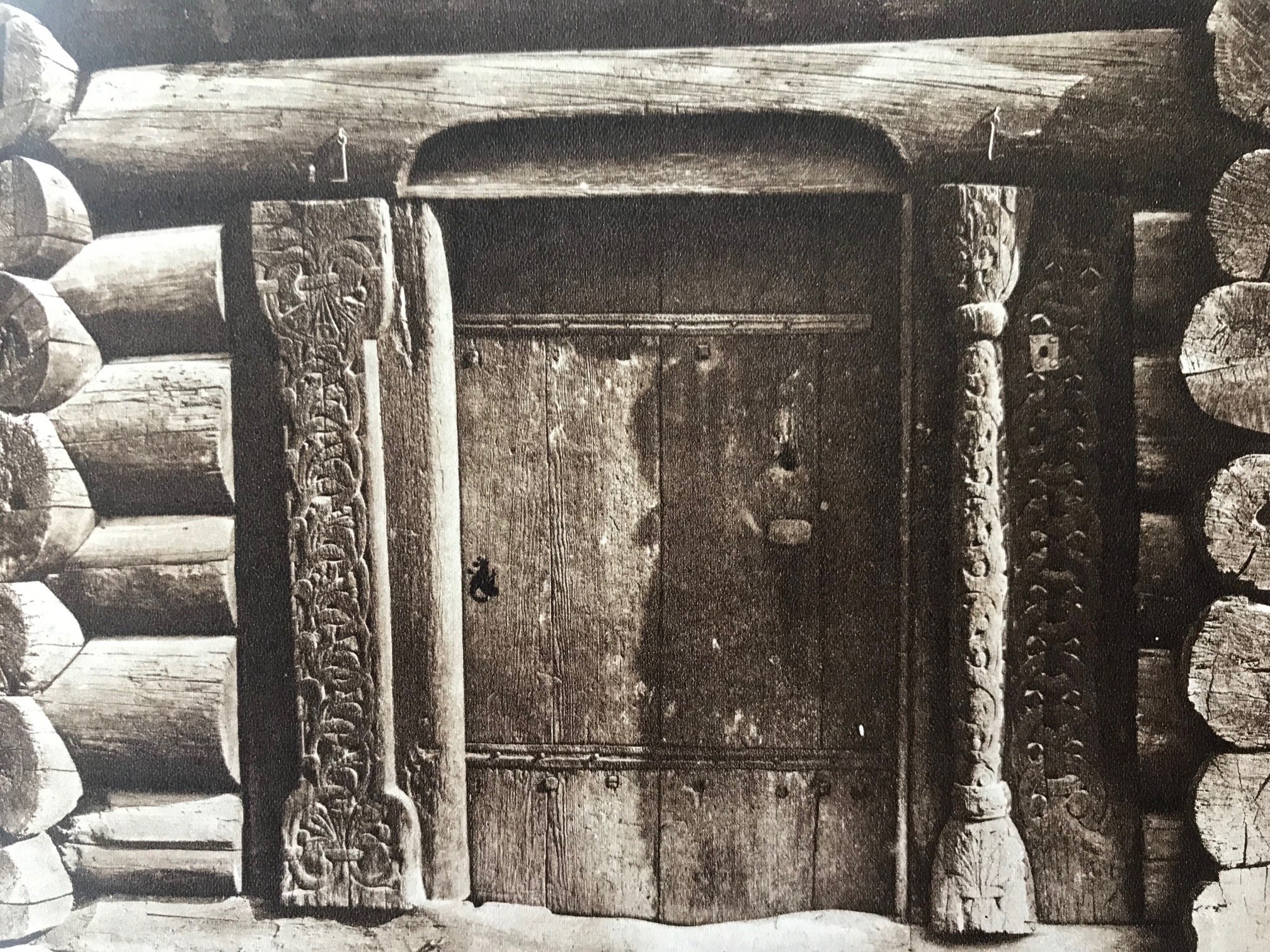

FOLKEMUSEUM BOOK

The book was published in Norway (1945). I remember first looking at it in the attic of the Minnesota family farm. Later, my grandmother and uncle gave it to me as a child. For a long time I thought the pictures depicted Sweden (and certainly was an integral part of how I imagined Sweden to be/look like for many years). The book is actually a collection of photos from a Norwegian open-air museum (the first of its kind was established in Stockholm, Sweden). Jämtland was a part of Norway for a time, with an ancient Viking trade route connecting Trondheim (coastal Norway) to Östersund (Jämtland, Sweden). The buildings represented in the book have more in common with northern mountainous Sweden than other parts of southern Sweden does with Jämtland.

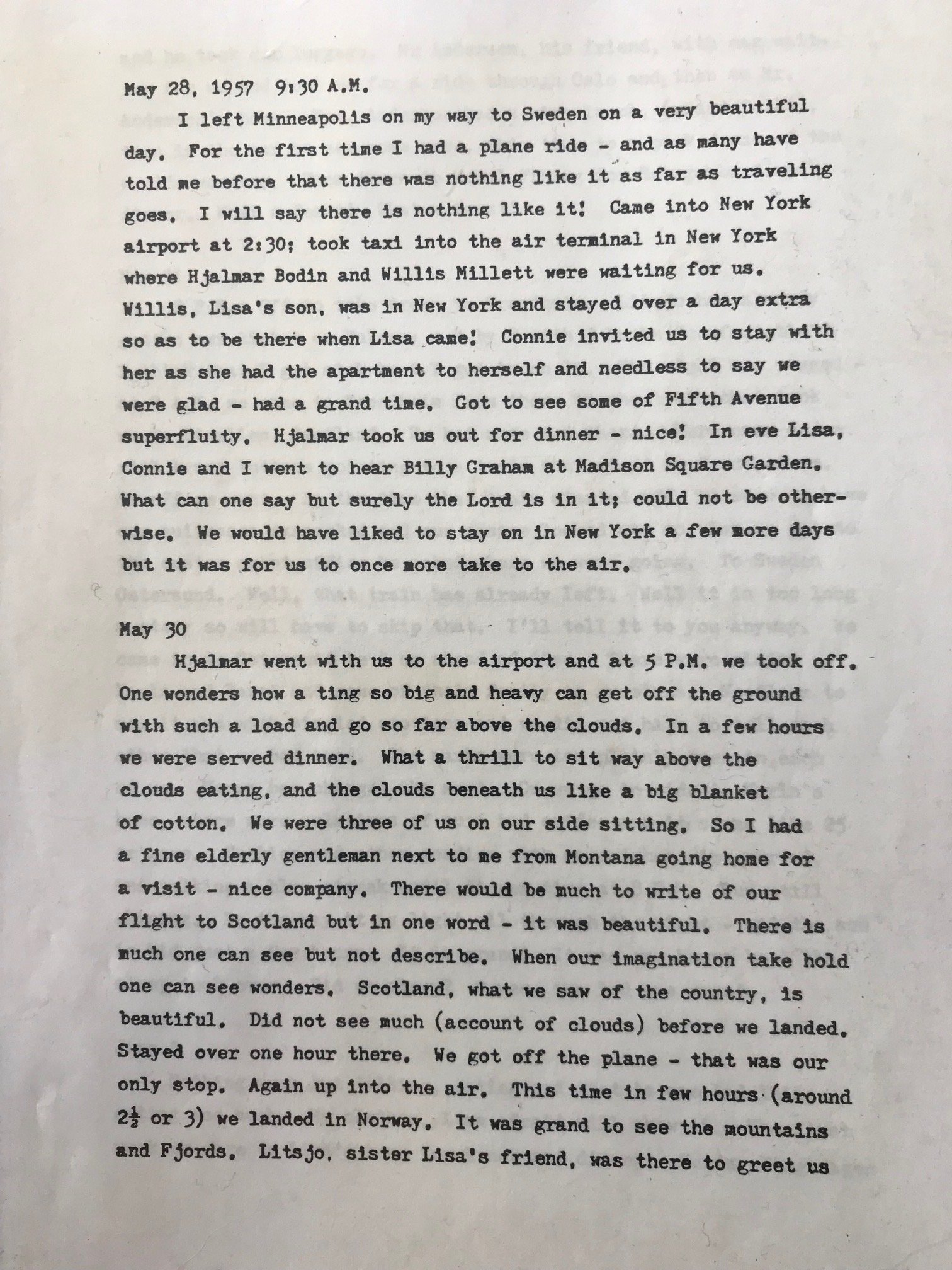

MARIE BODIN JOHNSON DIARY

Diary recording the artists’ great-grandmother's return visit to Sweden in 1957, after emigrating to the United States in 1910. Many place names and people are mentioned: remembering and revisiting places of origin, how place changes and is made and unmade, along with allusions to elements that cannot be recreated in a new land (time/temporal rhythms of summer in the far north, nature, relationship with Sámi friends and family, etc.).

ÖSTRA ARÅDALENS FÄBOD

Summer Farm - Jämtland - Oviksfjällen. Area in Jämtland where the women in our family worked for generations on fäbods (summer farms used in the mountains and forests in central/northern Sweden).

SWEDISH-AMERICAN FARM

Minnesota family farm preserved as it was in the 1930s. It was where our family first lived when moving from Sweden in 1910, and subsequently became a kind of immigration 'halfway house' for fellow Swedish immigrants throughout our grandmother's childhood. Thus, the farm acts as both an island of Swedishness—a portal connecting the U.S. to Sweden—and a site of erasure through its settler-colonial history, displacing the Anishinaabe people and indigenous histories/connections to the land. Our grandmother is buried in the farmyard, near the house, her remains embedded within the living soil, trees, and plants.